FORGOTTEN FUTURES

THE SCIENTIFIC ROMANCE ROLE PLAYING GAME

RULES

By Marcus L. Rowland

Copyright © 2005, portions Copyright © 1993-2002

Back to game index - Back to main index

By Marcus L. Rowland

Copyright © 2005, portions Copyright © 1993-2002

The first release of these rules was originally converted to HTML by Stefan Matthias Aust, to whom many thanks.

This document is a very large single file; a version split into several smaller files is also provided. Both should be accompanied by several files including larger versions of the game tables and a brief summary of the main rules for the use of players.

What will the future be like? Every generation has its own set of ideas and predictions. At the turn of this century most pundits thought that the mighty power of steam and electricity would usher in a new age of peace and prosperity. In the fifties the future was mostly seen as doom, gloom, and nuclear destruction. In the nineties we are obsessed with computers, and convinced that the future will revolve around information technology. Each of the earlier views was valid for its era; each was at least partially wrong. By looking at earlier guesses we may be able to discover what is wrong with our own vision of the future - and make even worse mistakes when we try to correct it! Forgotten Futures is a role playing game based on these discarded possibilities; the futures that could never have been, and the pasts that might have led to them, as they were imagined by the authors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Role playing games (usually shortened to RPGs) are story-telling games. One player is the referee who runs the game, and has an idea of what is to happen in the story, while the other players run characters in the story. Characters are defined by a name, a description, and a list of characteristics (such as 'MIND') and skills (such as 'Marksman'). Players describe the actions of their characters, while the referee describes everyone and everything they encounter. This may sound like an impossible job for the referee, but it's easy if players are prepared to co-operate.

The Forgotten Futures rules work well when dealing with the activities of normal people, but don't easily stretch to deal with magic, superhuman powers, and the like. Some of the appendices deal with magic, exceptional characters, melodrama, and other matters that the core rules don't cover; mostly this is material that was originally written for one or another of the Forgotten Futures settings, but seems to have more general application.

One aspect of the Forgotten Futures rules may annoy players who prefer high levels of violence; it is easy to get hurt or killed in all forms of weapon-based combat, it takes a long time to recover if you are wounded, and most wounds require medical treatment. This seems more realistic than the systems offered by some other RPGs, in which a character can be shot three or four times and still come back for more. If you dislike this approach please feel free to amend the injury system, but please DO NOT distribute modified rules.Introduction

I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past.

I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past.

Thomas Jefferson

Draw the blinds on yesterday and it's all so much scarier....

David Bowie

| About This Release

Since the game was originally published as shareware in 1993 there have been ten on-line releases, printed versions from two publishers, and conversions to pdf and html format. In all this the actual rules have stayed much the same. This release isn't going to change that; it's mainly tidying things up a little, adding in material originally written for one or another of the game settings which seems more generally useful, fixing some errors, improving layout, and generally making things more user-friendly. Most of the new material is in the appendices, but a few changes appear elsewhere. Where it's important the change is pointed out, one way or another. But you can still use any version of the rules to run anything written for the game. An important change is an acknowledgement of something that many referees will already know. In Forgotten Futures actions are resolved on a table which opposes "attacking" and "defending" skills, characteristics, or difficulty. Most referees find that they don't need to refer to the table after a game or two, since the rule behind it is extremely simple, and that it can even slow things down. This time around the text explains the rule, and a few references to the table have been changed so that they are applicable to both methods. The actual game mechanics - the values of skills etc., and the way that they interact - are unchanged. All of the material previously released or published for the game can be used without modification. All of the illustrations used come from the Forgotten Futures CD-ROM or one or another of the game releases, or were created for use with this release of the rules. Most have been cropped, reduced in size, or modified in other ways. |

The easiest way to understand an RPG is to see it played. In this example Bert is the referee; he's using these rules and a game background which assumes that the American Civil War ended in the formation of separate Confederate and Union nations. Eric is playing Captain Kirk T. James of the Confederate Zeppelin Squadron, Judy is Ella Mae Hickey, apparently a resourceful Southern belle but actually a resourceful Yankee spy, and Aaron is reporter Horace Mandeville of the Times (that's the London Times for American readers). They are heading towards a mysterious South American plateau, on the trail of the missing British explorer Professor Challenger (see Forgotten Futures III), but there have been problems:

The easiest way to understand an RPG is to see it played. In this example Bert is the referee; he's using these rules and a game background which assumes that the American Civil War ended in the formation of separate Confederate and Union nations. Eric is playing Captain Kirk T. James of the Confederate Zeppelin Squadron, Judy is Ella Mae Hickey, apparently a resourceful Southern belle but actually a resourceful Yankee spy, and Aaron is reporter Horace Mandeville of the Times (that's the London Times for American readers). They are heading towards a mysterious South American plateau, on the trail of the missing British explorer Professor Challenger (see Forgotten Futures III), but there have been problems:

Bert The airship is starting to rock from side to side, and pitching up and down in the cross winds from the hurricane. Eric I'll try to steer towards the eye of the storm. We'll drift with it until it ends. Bert How do you know where the eye is? Eric In this hemisphere storms spin anticlockwise. If I veer to the left, sorry, I mean port, while moving with the wind, I should go towards the eye. (Eric isn't sure, but it sounds plausible and is the sort of thing a real pilot would know. Bert isn't sure either, but knows that 'Kirk' should understand these things.) Bert Make your 'Pilot' roll, difficulty six. Eric (Rolls dice and consults table) No problemo. Gritting my teeth, I wrestle with the wheel and force the dirigible to its new heading. Aaron I pick up my pocket phono-recorder, slip in a new wax cylinder, and describe the captain's desperate duel with the elements. Bert Good idea, except you're still feeling airsick in the aft cabin and don't know what he's doing. Aaron I'll dictate a mood piece about airsickness instead. Let's see, how many different synonyms for the word "vomit" can I use... (starts to write list) Judy Ugh. Don't read it out loud. Bert Definitely not. Judy Once we're moving with the wind there should be less turbulence. Bert Yes, after a few minutes things seem to be getting quieter. Judy Kirk cut his head when the windscreen broke, didn't he? Bert You weren't in the control room, but yes he did. Judy Then I'll go forward and bandage Kirk's wounds. Bert I suppose he calls for your help through the speaking tube? Otherwise you wouldn't know. (Bert suggests this to keep the game moving. Players usually do better if their characters are together.) Eric Yes, as soon as things calm down enough to let go of the wheel for a few seconds. Aaron In that case I should feel better, so I'll tag along. Bert Roll for luck, to be there at the right time ..um... difficulty three. (Aaron rolls a 2, a success) OK, you get up and stagger forward in time to meet her. Judy I bat my eyelashes and ask him to carry my first aid kit. Aaron (speaking as Horace) Delighted to help, Miss Hickey. Bert You reach the bridge. Kirk is still at the wheel, and his forehead and arm are obviously badly gashed. Judy (as Ella Mae) Mah hero, you've saved us all! Eric (as Kirk) Shucks, it was nothing ma'am. Aaron (mimes speaking to recorder) Headline, Heroic But Modest Captain Defies Wounds In Hurricane Drama. Subhead, Southern Belle Angel Of Mercy. First paragraph: Captain Kirk T. James of the Confederate Zeppelin squadron today denied.. blah, blah, for a few paragraphs. Judy While he dictates I'll bandage the wounds. Bert Make a First Aid roll, difficulty four as he's lost a lot of blood. Eric Hey, I thought you said it was just cuts and bruises. Bert You didn't get her help straight away, and you've been bleeding for quite a while. It's now a flesh wound. (In this game prompt First Aid stops wounds getting worse, untreated wounds sometimes lead to additional damage. Some recovery time, and optionally the help of a doctor, is needed to restore health.) Judy Oh mah hero, let me tend to these awful cuts. (Rolls dice successfully) Eric Shucks, Ma'am, it's only a flesh wound. Ah feel better already. Bert Apart from bandages around your head and your left arm in a sling. You'll be walking wounded for at least a week. Eric Ouch. Judy When I pack my first aid kit afterwards I'll use my spy camera to take a picture of the maps on the bridge. Bert The camera concealed in your hat? It's the first chance you've had to use it, isn't it? Judy Uh-oh. Yes, it is. I have a bad feeling about this... Bert There's a loud whirring click, and the artificial flower at the front flaps out of the way, like the door of a cuckoo clock. The lens pops out on a concertina bellows and clicks, then retracts again. It takes two seconds. Eric Wow, really subtle. Do I notice this? (Eric - the player - knows that Judy's character is a spy, but Kirk - his character - is unaware of Ella Mae's real identity. A little schizophrenia is sometimes needed in an RPG) Bert Roll to notice. You too, Aaron. Difficulty six, I think, since her back is turned. Eric (Rolls dice) Rats - missed it. Bert Drowned out by the noise of the wind, perhaps. Aaron (rolls dice) Using my Detective skill I spot it, I think. (Horace is a reporter, so this skill - improved observational abilities - is naturally very useful) Bert Yes. What are you going to do about it? Aaron Nothing for now. It confirms what I thought when I saw her near the Marconi transmitter yesterday. I'll wait until we land, then try to get her to talk. An interview with a beautiful Yankee spy should sell a lot of papers! Bert Good thinking. Now, you seem to be in fairly clear air, and something big has just flown past the windscreen. Judy Another Zeppelin? Bert You're not too sure, but it looked like a pterodactyl....

In this example male players took male roles, and the female player took a female role. This is advisable if they feel uncomfortable playing a character of the opposite sex, but there is no other reason why players shouldn't run characters of different sexes, races, nationalities, or even species. The referee needs to take on a wide variety of roles, which will probably take in all of the above as a campaign progresses. At a few points in these rules it has been convenient to use the term "him" or "her" when describing something that is equally applicable to either sex. This is not meant to imply that either sex should be excluded from any activity. However, in historically accurate settings women may find themselved disadvantaged to some extent.

In this example male players took male roles, and the female player took a female role. This is advisable if they feel uncomfortable playing a character of the opposite sex, but there is no other reason why players shouldn't run characters of different sexes, races, nationalities, or even species. The referee needs to take on a wide variety of roles, which will probably take in all of the above as a campaign progresses. At a few points in these rules it has been convenient to use the term "him" or "her" when describing something that is equally applicable to either sex. This is not meant to imply that either sex should be excluded from any activity. However, in historically accurate settings women may find themselved disadvantaged to some extent.

| 1D6 | Roll one dice (one die if you feel pedantic) |

| 2D6 | Roll two dice and add the numbers |

| BODY | A characteristic, often abbreviated as B. |

| MIND | A characteristic, often abbreviated as M. |

| SOUL | A characteristic, often abbreviated as S. |

| Effect | Numerical rating used to calculate the damage caused by weapons and other forms of attack. |

| Average of.. | Add two numbers (eg characteristics) and divide by two. Round UP if the result is a fraction. Usually abbreviated as Av, e.g.AvB&S |

| Half of.. | Divide a number (usually a characteristic) by two and round UP. Usually shown as /2, e.g.B/2, 1D6/2 |

| Some skills are based on half the average of two characteristics. Add the characteristics, then divide by 4, then round up. e.g.AvB&S/2 | |

| +1 | Add 1 to a dice roll or other number. |

| +2 | Add 2 to a dice roll or other number. |

| -1 | Subtract 1 from a dice roll or other number. |

| -2 | Subtract 2 from a dice roll or other number. |

| 2+, 3+, etc. | 2 or more, 3 or more, etc. |

| Round | A flexible period of time during which all PCs and NPCs can perform actions. In combat a round is a few seconds, in other situations it might be a few minutes or hours. |

| Optional Rule | This means exactly what it sounds like; something that can be tacked onto the game if you want to use it, but isn't essential for play. Usually optional rules add extra realism, but make life harder for players or the referee, or involve complexities which you may wish to avoid. Most of the appendices are optional rules. |

| FF | Forgotten Futures (what else?) |

| Forgotten Futures I, II, etc. |

Numerous playtesters helped to develop the system or commented on its flaws. There are too many to name, my thanks to all.

Finally, literally dozens of people were helpful, supportive, and/or sympathetic to the ideas of this game, or encouraged its development. Again there are too many to name.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Each player will need at least one character, whose details should be recorded. You can use the HTML record form provided, one of the rather pretty .pdf record forms that were originally part of the printed version of the game, a spreadsheet template, or just write everything down on scrap paper. The example to the right shows the format that's generally used.

Players should record their names and the name (including any title or rank), sex, and age of the character. They may wish to give their characters aristocratic or military names and rank, academic honours, and the like; the referee must decide if this will cause problems.

Sex (Male or Female, and [optionally] sexual orientation) may be important in some game settings. Most scientific romances are based on ideas current in the early 20th century, and there are very few prominent female characters, apart from swooning maidens and an occasional competent scientist's daughter. It is rare to see a woman attain any influential business or academic status. In this setting a male adventurer is probably most useful. In a civilisation derived from a successful suffragette revolt women might have all the power, with men down-trodden or enslaved. In most scientific romance settings homosexual characters will encounter severe social problems.

Age is usually unimportant for adult characters; exceptionally young or old characters may be at a social disadvantage, otherwise there is no effect in game terms.

For "profession", write in something appropriate to the game setting; the referee should tell players if they have made an unsuitable choice. Since this game is based on a wide range of backgrounds almost anything might be useful.

Try to avoid professional ranks that will give players too much power, or restrict them too badly. A member of the Royal family is an example of both; someone accompanied by three or four detectives and a small army of servants can't personally be very adventurous. Wealthy characters are perfectly acceptable, but should not be able to buy their way out of every problem. Avoid occupations that restrict character freedom and mobility; an obvious example is a slave or a serf, but a clerk with no money, a businessman with a full work schedule, or a mother tied down by young children aren't much better off.

Example: Lady Janet Smedley-Smythe-Smythe

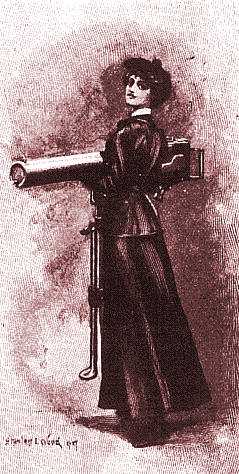

In a world whose science is based on H.G. Wells' "The First Men In The Moon", Lady Janet (shown, left, with her maid) is an eccentric explorer who defies the normal limits of her sex. She has participated in a series of daring interplanetary expeditions, using the latest model of Cavorite sphere-ship. She is single, 25 years old, and extremely rich. Her profession is recorded as "Immensely Wealthy Eccentric". The referee has no problem with this, because he wants the campaign to move between worlds, and sphere-ships are very expensive. Lady Janet and her adventures are used to illustrate many of the rules.

The next sections of the record are completed using character points.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Example: Lady Janet Smedley-Smythe-Smythe (2) The player running Lady Janet buys BODY [3] = 3 points MIND [4] = 5 points SOUL [4] = 5 points Total 13 points. 8 points are left. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

BODY (B) covers physical strength, toughness, speed, and dexterity.

MIND (M) covers all intellectual capabilities, reasoning, and observation.

SOUL (S) covers emotions, charisma, and psychic ability.

See below for full details of the effect of characteristics.

|

Skills are based on one or more characteristics, to which at least one point must be added. For instance, Actor is based on the average of MIND and SOUL, plus at least one point. A character with MIND [3] and SOUL [3] would get Actor [4] for one point, Actor [5] for 2 points, or Actor [6] for 3 points.

Brawling and Stealth are available at the values shown without spending points on them. Naturally they can be improved if points are spent.

See later sections for full details of the purchasing system and use of skills, and a more detailed explanation of each skill.

Example: Lady Janet Smedley-Smythe-Smythe (3)

Lady Janet doesn't bother to learn to fly her sphere-ship; that's what servants are for. Her hired pilot will be another player-character. She owns factories and other businesses which will need occasional attention, but her main interest is "collecting" (shooting) any alien animals she encounters. Obviously useful skills for this include Scientist and Marksman; she spends two points on each. For awkward situations First Aid, Athlete, Brawling and Stealth are useful; she has Brawling [3] and Stealth [2] for nothing, and spends a point each on First Aid and Athlete. Finally, any lady must be able to ride; how else does one fit into society? Ten points buy the following skills:No points are left.

Athlete [4] - 1 point

Brawling [3] - 0 points

Business [5] - 1 point

First Aid [5] - 1 pointMarksman [6] - 2 points

Riding [5] - 1 point

Scientist [6] - 2 points

Stealth [2] - 0 points

- Save for use in play.

Points can be used to improve skills at a later date, or optionally to improve the odds in emergencies. If points are saved for this purpose, double them and record them as bonus points.

Example: Lady Janet Smedley-Smythe-Smythe (4)

Lady Janet has no points left, so gains no bonus points.At the end of an adventure the referee should give players bonus points for successes, for unusually good ideas, for unusually good role playing, and anything else that seems appropriate. Try to give each player 3-6 points per successful adventure, less if they blow things completely. Bonus points should be noted in the Bonus box on the character sheet, and deleted as they are used.

For example, here is a genuine sample of dialogue that earned a player a bonus point:

1st player: "I say, isn't breaking and entering illegal?"Special thanks to Nathan Gribble for this gem.

2nd player: "Don't be silly, we're gentlemen!"

| Immensely Rich, Own Spaceship, Royalty Rich, Own Airship, Aristocrat Well off, Own car, Minor Title |

3 points each 2 points each 1 point each |

Under this system Lady Janet would need to spend eight points to get her special advantages. Use it if players seem to want to take unfair advantage of the referee. Referees who can take care of themselves are advised to omit it! One of the appendices covers more options for character background and traits.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Example: Lady Janet Smedley-Smythe-Smythe (5)

In addition to the sphere-ship, Lady Janet owns factories (the source of her wealth), an ocean-going yacht, a stately home, jewels, furs, several houses and apartments, and numerous cars and horses. Most of this stuff stays in the background, or is mentioned as it is needed. For example, when she wants to go to Rome she says she'll stay in a villa she owns; since this won't affect the game the referee has no objection. The referee does ask for a list of items she regularly carries on her person; these include a Derringer pistol, gold and jewellery (enough to make her a high priority target for any thief, although the referee doesn't mention that), and small flasks of laudanum (a powerful opium-based anaesthetic) and smelling salts. She wants to add a powerful rifle and shotgun; the referee rules that they might be kept in her sphere-ship, or carried when she's in the wild, but aren't routinely carried in more civilised areas. He also accepts that she has her own laboratories (mainly used for dissection) aboard the sphere-ship and in her mansion.

The weapons section is used to record weapons that the character routinely carries. The columns list the weapon's name, whether it is capable of multiple attacks, the Effect number which determines how much damage it can cause, and the results of any damage caused. For now it isn't necessary to worry about the use of this system; it's explained in the section on combat below. Weapons are also listed below.

Example: Lady Janet Smedley-Smythe-Smythe (6)

Lady Janet has several weapons; her hands and feet, and the guns she owns. These need to be recorded on the character sheet. The only hard part of this process is calculation of the Effect number for some weapons, which may be dependent on BODY or one or another skill. Lady Janet uses the Brawling skill to fight with her hands and feet. For these attacks the Effect number is equivalent to her BODY, 3. She has several firearms; all of them have fixed effect numbers determined by the size and speed of the bullet.

The section marked "Wounds" is left blank for use during play. Note that this is the wound chart for humans and animals of roughly human size and toughness; some animals use different charts.

BODY represents general physique, well-being, stamina, and speed. If characters expect to spend a lot of time in combat, or performing manual labour, BODY should be high. Inanimate objects also have BODY. BODY is NOT necessarily indicative of size or weight; it's possible for something to be physically small or light and still have high BODY (e.g. a bantam weight boxer, a steel key), or big and have low BODY (e.g. a fat invalid, a greenhouse).

MIND covers all mental skills and traits including intelligence, reasoning ability, common sense, and the like. Anyone in a skilled job probably needs high MIND. MIND is also important in the use of most weapons.

SOUL covers artistic abilities, empathy, luck, and spiritual well-being. If SOUL is low the character should be played as aloof, insensitive, and unlikeable (as in the phrase "This man has no soul"); if high, the character does well in these areas. It is also used for other forms of human interaction, such as fast-talking, acting ("A very soulful performance"), and other arts (including martial arts). If your SOUL is low better not try to con anyone, and forget about learning baritsu or karate.

Normal human characteristics are in the range 1-6, with 1 exceptionally poor, 3 or 4 average, and 6 very good, the top percentile of normal human performance. Player characters may have characteristics of 7 at the discretion of the referee ONLY; this is freakishly good, far better than normal human performance. For example, a gold-medal Olympic athlete might have BODY [7], a Nobel Prize winner MIND [7].

Characteristics cannot normally be improved; under really exceptional circumstances changes might be allowed, but this is a once in a lifetime event. For example, someone discovering the fountain of eternal youth might gain extra BODY, but there should be a price to pay; reduced MIND or SOUL, hideous deformity, and the like. In the unlikely event of an increase in any characteristic, any skills already derived from it (see below) should be recalculated and (if necessary) improved.

Characteristics may sometimes be reduced. For instance, someone crippled after a fall might lose BODY, someone suffering a severe head injury might lose MIND. SOUL might be damaged by insanity or drug abuse. If any characteristic is reduced, recalculate the values of all skills derived from it.

Depending on circumstances, characteristics may be used against other characteristics, against skills, or against an arbitrary "Difficulty". Skills give an edge in most of these situations, as explained in later sections, but it's occasionally necessary to use them directly. For this, and for all other use of characteristics and skills, roll 2D6 on the table below:

If the result is below 12 and less than or equal to the number indicated on the table, the attempt succeeds. A dash (-) indicates that there is NO chance of success, otherwise 2 is ALWAYS a success and 12 is ALWAYS a failure.

If you prefer to do without the table a little mental arithmetic can be used as follows:

Optional Rule: For both methods, to improve the odds very slightly assume that any roll of 2 is a success, regardless of Difficulty. This means that there will always be at least a 1 in 36 chance of success.

Whether the table or mental arithmetic is used, the referee may prefer to keep the target value a secret, and simply tell the player if the result is a success or failure.

For both methods, if the result is EXACTLY the number needed to succeed, the attempt has come very close to failure; referees may want to dramatise this appropriately. If the number rolled is much lower than the number needed to succeed, the referee should emphasise the ease with which success was achieved. Similarly, a roll just one above the number needed for success should be dramatised as a very near thing that came within an ace of succeeding, a very high roll as an abject failure. These dramatics aside, any success is a success, any failure a failure.

Example: Breaking down a door

Example: Arm Wrestling

This system isn't perfect. For example, a man with BODY [3] theoretically has a 1 in 36 chance of lifting a BODY [10] elephant; in practice the referee should make this task much harder. Referees should be firm if players want to do something that's physically impossible, or make them tackle the job in smaller chunks. "Pass the saw, I need to cut up this elephant..."

Example: It's Up His Sleeve!

Example: I Can Take It...

At the discretion of the referee ONLY players may spend bonus points to temporarily modify an attacking or defending value as appropriate. Players must declare that they are doing this, and mark off the point(s) used, before the dice are rolled.

This rule does NOT mean that you can spend points to perform the physically impossible. No matter how many points are spent, a BODY [1] weakling will not lift an elephant single-handed. Regardless of points spent, a 12 is still a failure.

Using Characteristics

Attacking

Characteristic,

Skill, Effect, etc.Defending Characteristic, Skill, or Difficulty 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 1 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - - - - - - - - - 2 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - - - - - - - - 3 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - - - - - - - 4 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - - - - - - 5 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - - - - - 6 11 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - - - - 7 11 11 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - - - 8 11 11 11 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - - 9 11 11 11 11 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - - 10 11 11 11 11 11 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 2 - To do anything roll 2D6:

All other feats of strength should use BODY to attack BODY. If several characters want to co-operate in a feat of strength, take the character with the highest BODY and add the BODY/2 of each additional person aiding.

Fred (BODY [4]) wants to break a household door (BODY [6]). The first attempt is a roll of 7.

7 (the roll) + 6 (the door's BODY) - 4 (Fred's BODY) = 9

The kick's a failure, and the door rattles but stays shut.

After a brief rest Fred kicks the door again. On a 2 the lock breaks. The referee dramatises this by describing the wood splintering and the knob flying across the room and shattering a priceless Ming vase.

Fred (BODY [4]) and Nigel (BODY [2]) are arm wrestling. In each round each should roll BODY as attacker with the other character's BODY as defender.

Fred (BODY [4]) and Nigel (BODY [2]) are arm wrestling. In each round each should roll BODY as attacker with the other character's BODY as defender.

Round 1: Fred and Nigel both roll 10, much too high to succeed. Nothing happens, apart from a slight flabby quivering of opposed muscles.

Round 2: Fred and Nigel both roll 3, and succeed. Again, nothing happens. Since both succeeded this is described in terms of bulging muscles, a clash of titans.

Round 3: Fred rolls 10 and fails, Nigel rolls 2 and succeeds. Nigel smashes Fred's arm to the table and wins the match.Example: Excuse Me, Where Is The British Consul?

Lady Janet has been captured by Venusian savages who have decided that she is their long-awaited god (her gender isn't obvious to Venusians). They have no common language. The referee decides that her SOUL [4] must be used against the native chief's SOUL [5] to make her manner sufficiently forceful, and ensure her release. On a 2 the natives build a sedan chair to carry her back to the sphere-ship.

Note: Sadistic referees might prefer to make players act out scenes like this...

On their way back to the ship the native witch doctor decides that Lady Janet's charismatic presence undermines his authority. He challenges her to a duel of magic (actually conjuring), using his skill Acting [6]. She must use her MIND [4] to spot his tricks. He begins by making a fruit "disappear"; on a 3 she notices that he's tucked it into a fold of his loincloth, and points out the bulge to the audience. This causes so much lewd merriment that the duel ends in his abject defeat.

The wily witch doctor has persuaded the chief that Lady Janet must be tested again. This time it's a test of endurance; she must put her hand into a jar of stinging insects. Their stings are extremely painful but do no permanent damage. Lady Janet must use her MIND [4] to attack an arbitrary difficulty of 8.

This is a tough test; on a 6 she fails, pulling her hand out before the test ends. Fortunately she has the sense to grab a handful of insects and throw them at the witch doctor; he also fails, and starts to scream as they sting him. The chief decides that nothing has been proved.

Incidentally, the referee might instead have asked for a roll of AvB&M, rather than just MIND, to check if the character has the will-power and endurance to overcome the pain, or SOUL to check if the character has the courage to endure it.BIG Numbers

If attacking and defending values are both above twelve, divide both by a number which reduces them both below 12. For really large numbers (Godzilla versus New York, an H-Bomb versus the Rock of Gibraltar) division by 50 or 100 may be needed, but in most cases dividing by a smaller number (such as 2,3,4,5, or 10) should do the job. Round numbers up if the result is a fraction. In any campaign with ships, spacecraft, land ironclads, or dirigibles this system may become important in combat.Example: Tom Sloth And His Pneumatic Coveralls (1)

Tom Sloth, the brilliant but somewhat misguided engineer, has developed a mechanical exoskeleton which can be worn over normal clothing. It looks like a pair of silver coveralls, and will theoretically let him lift things as though his BODY (normally 5) is 30. He decides to test it by lifting an elephant at the zoo. The exoskeleton attacks with BODY [30], and the referee has decided that lifting an elephant will be difficulty 20. Neither number is under 12, so he divides both by 3 to make them fit. Now the attacking force is 10 and the defending BODY rounds up to 7.

On a 3 Tom lifts the elephant; unfortunately its weight is now attacking his ankles and wrists, which aren't boosted by the power of the coveralls... BODY 10 is attacking Tom's unmodified BODY 5; the weight will cause him serious harm on an 11 or less!Improving The Odds

Example: She's Buying A Stairway To Heaven...

Lady Janet and the Venusians are being chased by a huge predator, and want to take to the trees to avoid it. The Venusians are natural climbers, and sprint up the trees without any trouble, leaving Lady Janet stranded four feet below the lowest branch. She tries to jump (Athlete [4] attacking difficulty 5) and fails on an 8. The predator roars and pads toward her. Before trying again she spends two bonus points to temporarily boost her Athlete skill to 6. Propelled by a sudden surge of adrenalin she zooms up the tree, passing the Venusians before they're half-way up.Common Characteristic Rolls

|

All of the above situations have something in common; they should not occur frequently, and must not be an essential stage in an adventure. There must always be an alternative which does not rely on the luck of the dice. Sometimes players get unlucky in situations where their characters should succeed; in one play-test five adventurers failed to hear something at difficulty 3, and an extra clue was needed to put them back on the right track.

All of the above situations have something in common; they should not occur frequently, and must not be an essential stage in an adventure. There must always be an alternative which does not rely on the luck of the dice. Sometimes players get unlucky in situations where their characters should succeed; in one play-test five adventurers failed to hear something at difficulty 3, and an extra clue was needed to put them back on the right track.

Example: It's Behind You...

A Venusian predator has chameleon-like camouflage abilities. One is about to pounce on the witch doctor's son, and Lady Janet is the only person with a chance to spot it. She must roll MIND against difficulty 6 to notice. On a 3 she succeeds and yells just in time to save his life, finally earning the witch-doctor's friendship. The referee might instead have had her roll against the creature's Stealth skill.

Skills are initially calculated from one or more characteristics, with the number of points spent added to the result. For instance, Marksman (the use of all forms of hand-held firearm and other hand-held projectile weapons such as crossbows) is based on MIND. Acting is based on an average of MIND and SOUL. Skills may be raised to a maximum value of 10.

Example: Buying SkillsCharacters automatically have two skills at their basic values without spending points: Brawling and Stealth. Naturally points can be spent to improve them. Optionally additional skills may be made available at their basic values; see Free Skills, below.

While generating Fred (MIND [4], SOUL [2]) a player adds two points each to the skills Acting and Marksman, and one to Linguist.

Marksman will be rated at MIND +2.

Acting will be rated at the average of MIND and SOUL +2.

Linguist will be rated at MIND +1, with his native English and Linguist/2 other languages known.

This is recorded on his character record as Marksman [6], Acting [5], Linguist (Modern Greek, German, French) [5]

Example: It's All Greek... (1)Dice rolls should be made if the character is working under unusual or difficult conditions, under stress, or in immediate danger. They are always used in combat. Usually a skill is used against one of the following:

Fred has the skill Linguist [5] and knows Greek. He is buying a box of matches in a shop in Athens. No dice roll is required.Example: ...If Gills Are Green Go To Section 6b...

Lady Janet wants to identify Venusian foods that are safe to eat. Her backpack contains a copy of the Oxford Guide To Extra-Terrestrial Vegetables, and she is using its key to identify a curious warty fungus. This is routine easy use of her Scientist [6] skill and no roll is needed.

Example: Trouble At T'millBonus points can usually be spent to improve skill rolls, exactly as they are used to improve characteristic rolls.

On her return to Earth, Lady Janet finds that one of her factories is on the verge of bankruptcy. She travels to Lancashire to investigate, using a series of Business skill rolls to overcome the Business skill of a crooked manager who has been bleeding the company dry.

Once the villain is unmasked she should theoretically use her Business skill to unravel years of tortuously complicated accounts and restore the factory to prosperity. In practice, she uses the skill to weigh up the merits of several candidates and hires another manager.Example: It's All Greek... (2)

Fred is still in Athens, and wants to buy a box of silver bullets, ten crucifixes, a certified genuine saint's relict, and a Mk 4 Carnacki Electric Pentacle. When the police arrest him as a suspected lunatic he will need to make several Linguist rolls against Difficulty 6 to explain his need for these items, and at least one Acting roll at Difficulty 8 to persuade them to let him go.

Example: What If I Press This Button?

Lady Janet's sphere-ship is hit by a meteor. Her pilot is knocked out, and the ship is veering wildly off-course. No-one else aboard has the pilot skill; the referee decides that Lady Janet has been in the control room often enough to have a sketchy idea of piloting techniques. She will use the skill at AvB&M/2, or Pilot [2]. Normally the roll to restore the ship to its correct course would be against difficulty 4; because she isn't properly trained, the referee changes that to difficulty 8. On a 2, she just succeeds.

Bonus points may not be used to help in this situation.

Some projects simply require routine use of a skill for a prolonged period, with any failure extending the time. For example, the creation of an average quality monolithic sculpture might need five Difficulty 6 Artist rolls at intervals of a month; any failure leads to major revision of the work, extending the time needed by two months. The project is completed when the fifth successful skill roll is made.

Sometimes practice is all that is needed. This is especially true when learning languages.

Example: Que..?

Fred doesn't understand Spanish. During an adventure in Spain he tries to learn the language; since he already knows some related languages the referee rates this as difficulty 8 after a week, Difficulty 7 after two weeks, and so forth. A lucky roll of 2 allows Fred to learn the language in a week, and it's added to the list on his character record.

NOTE: This considerably underestimates the difficulty of learning a new language. Linguistic problems are not usually much fun to role-play, unless you particularly want to inflict an unreliable translator on characters, and most scientific romances either ignore them completely or assume that their heroes will easily teach the natives English! The Astronef stories, in FF II, are a little more honest; after weeks of contact with the cultures of Venus and Ganymede, the hero and heroine remain completely ignorant of the native languages. In The Lost World (FF III) the heroes spend weeks with an Indian tribe without learning much of their language.

NOTE: This considerably underestimates the difficulty of learning a new language. Linguistic problems are not usually much fun to role-play, unless you particularly want to inflict an unreliable translator on characters, and most scientific romances either ignore them completely or assume that their heroes will easily teach the natives English! The Astronef stories, in FF II, are a little more honest; after weeks of contact with the cultures of Venus and Ganymede, the hero and heroine remain completely ignorant of the native languages. In The Lost World (FF III) the heroes spend weeks with an Indian tribe without learning much of their language.

Research projects, such as the development of a new invention, are resolved a little differently. The referee should decide how difficult the work will be, and how long it will take, then require a series of skill rolls of gradually increasing difficulty, repeated until the final difficulty level is reached. The same procedure might also be used for creation of an artistic masterpiece.

Example: What Goes Up...

Lady Janet's colleague Professor Polkington wants to develop a new antigravity paint and smash the Cavorite monopoly. The referee decides that this project will start at Difficulty 5, but will eventually be Difficulty 10, and each stage of the project will take 1D6 months; initially 4 months.

At the end of 4 months the skill roll fails. Polkington has achieved nothing, apart from shutting off a few dead ends. The referee rolls 1D6 again, and determines that the project will stay at Difficulty 5 for another 3 months. This cycle is repeated until there is a success, then the difficulty is raised to 6 for the next round of attempts. Difficulty continues to escalate until Polkington eventually overcomes difficulty 10 to complete the synthesis. Most of this occurs off-stage between adventures, but occasionally it impinges on the game; for instance, the referee might tell players that Polkington must spend the next 48 hours in his laboratory to finish the current round of experiments, depriving them of his skills at a vital moment, or that he will need a rare chemical or manuscript for the next step. Finding the missing ingredient might be an adventure in itself.

The referee need not say that characters are attempting the impossible, but it's advisable to drop a few hints if serious amounts of time are being wasted on a completely fallacious idea.

| Under the rule above, additional skills based on high characteristics cost more than skills based on low characteristics. Optionally the referee may allow adventurers to add skills at less than base value with an appropriately reduced bonus point cost. By the time the skill reaches base value it will cost much more than the usual method, but this allows players to spread the cost over several adventures. For instance, a character with MIND [5] might add Marksmanship at a low level; just enough to shoot for the pot, not to shoot for the British Olympic team. In this example the player might choose to take Marksmanship [3] for 6 points, not Marksmanship [6] for 12 points. Once acquired such skills can only be improved by the normal process, and one point at a time. Referees are also advised to limit the number of below-base skills acquired to MIND/2; once skills are up to the usual base value they don't count towards this limit. The "difficult skills" described above may not be acquired this way. |

Example: Everyone's Jumping...

In a world based on a revival of ancient Greek customs, it's customary for every citizen to participate in the Olympics or face ostracism. All characters should have the Athlete skill automatically at BODY; extra points push it to BODY+1 etc.

Skills are listed in the following format: Name, basic value (to which the points spent should be added), and explanation. The following abbreviations are used:

Skill List

This list does not represent every possibility; it is just a selection of the most useful skills. Please feel free to add more, to change values and costs, or otherwise mess things up, but DON'T distribute modified versions of this file!

B = BODY, M = MIND, S = SOUL, Av = Average, / = Divided by

For example:

Skills marked with an asterisk are automatically acquired at their basic values.

AvM&S = average of MIND and SOUL (round up) M/2 = MIND divided by 2 (round UP) AvB&S/2 = average of BODY and SOUL divided by 2 (round UP)

Actor — Basic Value: AvM&S

Any form of stage performance. If more than one point is spent you are good enough to earn money from one specialised type of performance, such as Operatic Tenor, Conjuror, Ballerina. This skill is also useful for confidence tricks. E.g. Actor (Juggler)

Any form of stage performance. If more than one point is spent you are good enough to earn money from one specialised type of performance, such as Operatic Tenor, Conjuror, Ballerina. This skill is also useful for confidence tricks. E.g. Actor (Juggler)

Artist — Basic Value: AvM&S

Athlete — Basic Value: B

Babbage Engine — Basic Value: M

Brawling — Basic Value: B *

Business — Basic Value: M

Detective — Basic Value: AvM&S

Trained in the art of observation; good at spotting small details, noticing faint scents, little clues, unusual behaviour, etc. Can be used as an improvement over normal observation rolls, and sometimes in place of an Idea roll, or in place of the Psychology skill. Specialities might include forensics, interrogation, etc. E.g. Detective (Bertillon identification system)

Trained in the art of observation; good at spotting small details, noticing faint scents, little clues, unusual behaviour, etc. Can be used as an improvement over normal observation rolls, and sometimes in place of an Idea roll, or in place of the Psychology skill. Specialities might include forensics, interrogation, etc. E.g. Detective (Bertillon identification system)

Doctor — Basic Value: M/2

Driving — Basic Value: AvB&M

Car chases and other vehicle pursuits should be resolved by using the skill of the chasing driver to attack the skill of the fleeing driver. Attempts to follow cars should be resolved by use of the tailing driver's skill to attack the observational ability (or Detective skill) of the lead driver. The performance of the vehicles may also be a factor, of course. First Aid — Basic Value: M

Linguist — Basic Value: M

Marksman — Basic Value: M

Martial Arts — Basic Value: AvB&S/2

This is by far the most powerful unarmed combat skill in this game, and is not necessarily appropriate to the scientific romance genre (although Sherlock Holmes was a master of Baritsu, an obscure Oriental martial art; see the article The New Art of Self-Defense on the FF CD-ROM). Players should only be allowed to take the more obscure martial arts at the referee's discretion, and only if they can devise a background to explain acquisition of this skill. Referees can make it a little less useful by adopting one or both of the following optional rules:

This is by far the most powerful unarmed combat skill in this game, and is not necessarily appropriate to the scientific romance genre (although Sherlock Holmes was a master of Baritsu, an obscure Oriental martial art; see the article The New Art of Self-Defense on the FF CD-ROM). Players should only be allowed to take the more obscure martial arts at the referee's discretion, and only if they can devise a background to explain acquisition of this skill. Referees can make it a little less useful by adopting one or both of the following optional rules:

Mechanic — Basic Value: M

Medium — Basic Value: S/2

Melee Weapon — Basic Value: AvB&M

Military Arms — Basic Value: M

Morse Code — Basic Value: M

Pilot — Basic Value: AvB&M/2

Psychology — Basic Value: AvM&S

Riding — Basic Value: AvB&S

Scholar — Basic Value: M

Scientist — Basic Value: M

Stealth — Basic Value: B/2 *

Thief — Basic Value: AvB&M/2

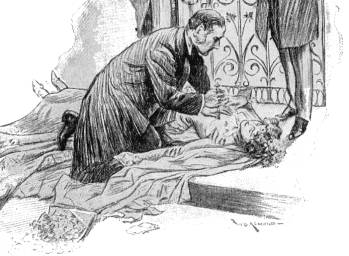

Wounds

Each character and NPC has a Wounds record, which indicates the general severity of wounds taken. It is possible (and sometimes easy) to go from "uninjured" to "dead" as the result of a single wound.

Wounds B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] |

|

The table shows the effects of wounds. Temporarily reduce the value of BODY and BODY-related skills by the value shown, but not below a minimum of 1.

Example: It's Only A Flesh Wound...(1)

During a visit to a German Duke's estate, Lady Janet takes part in a boar hunt. During a sudden storm she is separated from the rest of the hunters, and loses her gun in a thicket.

As she trudges home she disturbs a boar and is badly cut by one of its tusks. In the next round she tries to fend it off by beating it with a fallen branch. Normally she would use her Brawling [4] skill for the attack; because she has a flesh wound this is reduced to Brawling [3].

First Aid stabilises wounds and prevent them getting worse. On a successful roll against the recovery Difficulty of the wound, there is no possibility of deterioration. For example, this might involve splinting a broken leg, disinfecting and bandaging a wound, or putting cold tea (a common Victorian remedy) or ice onto a burn. Multiple wounds must be treated separately; for instance, someone with a Flesh Wound and an Injury, or with two Injuries, would need each treated separately.

First Aid stabilises wounds and prevent them getting worse. On a successful roll against the recovery Difficulty of the wound, there is no possibility of deterioration. For example, this might involve splinting a broken leg, disinfecting and bandaging a wound, or putting cold tea (a common Victorian remedy) or ice onto a burn. Multiple wounds must be treated separately; for instance, someone with a Flesh Wound and an Injury, or with two Injuries, would need each treated separately.

Without first aid the wound may eventually deteriorate; roll the recovery Difficulty against the patient's BODY, if the result is a success the wound will get worse. Flesh wounds become Injuries and Injuries become Critical (usually as fevers and illnesses such as gangrene) if they get worse.

The Doctor skill acts like First Aid, and also speeds healing. If a successful roll is made recovery time is halved. Since the Doctor skill usually begins at a lower level than First Aid, devoted healers may wish to take both skills.

To recover from wounds without medical help, roll BODY against the recovery difficulty - AFTER the minimum recovery period. If the result is a success, the wound is healed. If the result is a failure, the illness drags on for another period before the roll can be made again.

Example: It's Only A Flesh Wound...(2)

Lady Janet has a flesh wound. She bandages it herself, using First Aid [5] against recovery Difficulty [4]. On a 9 she doesn't do a good enough job of cleaning the wound and applying pressure to prevent further bleeding.

She rolls BODY [3] against Difficulty [4]. On a result of 10 the wound gets worse; by the time she reaches help Lady Janet is bleeding severely, and must spend some time in bed. Her doctor fails to help, so her first roll for natural recovery is made after a month. Fortunately she succeeds and finally heals.

Death is death, and is usually permanent. In some settings there may be some rationale for reanimation or resurrection, but in most games there is no recovery. The referee should explain if this applies.

Some examples of common forms of injury follow the combat rules below; they are clearer if you understand some details that are introduced in the combat rules.

The combat rules take up a large chunk of this file; this does NOT mean that they are the most important aspect of the game - it just means that they are a little more complicated than other sections. DON'T make the mistake of thinking that every adventure must involve several fire-fights!

The combat rules take up a large chunk of this file; this does NOT mean that they are the most important aspect of the game - it just means that they are a little more complicated than other sections. DON'T make the mistake of thinking that every adventure must involve several fire-fights!

These rules borrow an idea that is found in some war games. All the events in a combat round occur simultaneously. If ten people are firing guns, all of them fire BEFORE the results are assessed. You can shoot a gun out of someone's hand, but he will have a chance to shoot you before he loses it. Attacks are usually a use of skill against a defence; if the attack penetrates the defence, the damage is determined by use of the attack's Effect against the BODY of the target. All of these concepts are explained in more detail below.

The following things can be done in a combat round

Anyone taken completely by surprise CANNOT fight, move, or dodge in the first round of combat, but CAN perform a simple action. For example, intruders would have a round to attack someone who was standing a few feet from an alarm button; he would not have time to

get to it first. They could not stop him pressing the button if he already had his hand on it. By definition, someone with a weapon in his hand pointed at an attacker is NOT taken by surprise!

Combat Rounds

A combat round is a period of approximately five seconds in which combat occurs. In this time punches might be exchanged, shots fired, and so forth.

If you don't want to move or perform any action apart from the attack itself there is a bonus on the attack, but you do NOT fire first.

A normal human can walk about ten feet, or run twenty. On a Difficulty 6 BODY or Athlete roll, or on expenditure of a bonus point, this can be pushed to thirty feet.

OR

Referees may OPTIONALLY allow two actions, or an action and a movement, in a round; for instance, opening a door and diving through.

THEN

THEN

Resolving Attacks

Attacks are resolved in the following stages:

Rolling To Attack

|

One modifier may need explaining, since it is frequently misunderstood; machine guns are a little less accurate than other firearms, but more than make up for it by firing LOTS of bullets, increasing the chance of a hit over that for a normal gun. This is the main reason why automatic weapons are used. The idea that machine guns rarely hit and do less damage than other firearms is a myth. Even when used for single shots they are no less accurate than other weapons of similar size.

Example: Collecting A Specimen (1)

Lady Janet (Marksman [6]) wants to "collect" a Ganymedan lion. The lion isn't defending itself, so she must fire the shot against a basic difficulty of 6. The lion is immobile (+1) and large (+1), so her skill would normally be modified to 8; unfortunately it's a long way off (-1), and has skin coloration that makes it harder to see (-1), so the skill stays as Marksman [6]. On an 8 the shot misses; the lion is startled and runs away.

In the second round the lion is moving (-1), but Lady Janet didn't move (+1). The lion is still big (+1) and isn't trying to dodge or hide, and is no longer camouflaged, but it's still a long way off (-1), so Lady Janet uses an effective Marksman [5] for her next shot. On a 4 it's an easy hit.

Example: Take That You Cad! (1)

Bobby and George have decided to settle their differences in a boxing match. Both have BODY [4] and the Brawling [5] skill.

In the first combat round Bobby dodges and weaves (-1) then tries to punch the immobile (+1) George; George stays still (+1) and tries to hit the dodging (-2) Bobby when he gets close.

In this round Bobby has an effective skill of Brawling [5], George an effective skill of Brawling [4]. On a 3 Bobby easily breaks past George's guard, but on a 2 George also hits Bobby.

Some attacks can be used via two or more skills; for example, a longbow might be used via the Marksman or Martial Arts skill, a club via the Brawling or Melee Weapons skill. Use whichever skill is best. If all else fails weapons may be used via characteristic rolls; these are usually poorer than skills.

Defences may also be based on skills or characteristics; for example, someone might try to avoid an arrow by ducking (BODY versus the attacking skill), by hiding (Stealth skill), or by use of the Martial Arts skill to catch it! If no better skill is available, the basic defending value is 6.

If the result of any attack is a success, some damage occurs. Roll for damage as described below.

|

All attacks have an Effect number. For hand-to-hand weapons, martial arts, and other unarmed combat skills it is either the skill level or the user's BODY plus a bonus; for example, a club gains most of its power from the user's strength, and has an Effect equal to the user's BODY +1. A fencing foil, like all swords and daggers, has an Effect equal to Melee Weapon skill. For firearms the Effect number is usually intrinsic to the weapon, and thus independent of the user's skill or BODY.

Damage is determined by using the Effect number to attack the target's BODY. The result of this roll will sometimes be a failure; this is interpreted as minimal damage for the weapon, from column A of the weapons table. While this is always preferable (for the victim!), many weapons have a flesh wound or worse as their minimal damage.

If the result is a success, but more than half of the result needed for a success, check column B of the weapon table.

If the result is a success, and the dice roll is less than or equal to half the result needed for a success (round DOWN), check column C of the weapon table. If in doubt, use the table to the right to calculate which damage column is used.

Example: Collecting A Specimen (2)

Lady Janet's hunting rifle is recorded as follows:This means that it does the following damage:

Weapon Multiple Effect Damage Targets A B C Big Rifle No 8 F I C/K

A: Flesh wound

B: Injury

C: Roll the Effect against BODY again; if the result is a failure the injury is critical, otherwise it's a kill.

Effect [8] attacking BODY [8] succeeds on a 7 or less.

If the result is an 8 or more the lion suffers a flesh wound.

If the result is 5-7 the lion is injured.

If the result is 2-4 the lion is critically injured or killed.

On 4, then 6, the lion is killed.Example: Take That You Cad! (2)

Both combatants are using fists, which are rated as follows:There is no reason to modify these results, so both must use BODY [4] against BODY [4].

Weapon Multiple Effect Damage Targets A B C Fists No BODY B B KO

On a 9, George just grazes Bobby. On a 2, Bobby catches George with a perfect right hook and knocks him out.

Machine guns use a special rule for Effect. If they are used on more than one target, the Effect is reduced by 2. The attacker must roll separately to hit each target, and to damage the victim if the attack is successful. It's easy to abuse machine guns; players often say that they are trying to shoot at victims in two or three different areas, which should not be allowed. Shooting at several targets in one direction (such as a group of men running along a corridor) is acceptable, but the targets in front will conceal those behind, or at least reduce the Effect. They are powerful weapons, but not all-powerful.

Machine guns use a special rule for Effect. If they are used on more than one target, the Effect is reduced by 2. The attacker must roll separately to hit each target, and to damage the victim if the attack is successful. It's easy to abuse machine guns; players often say that they are trying to shoot at victims in two or three different areas, which should not be allowed. Shooting at several targets in one direction (such as a group of men running along a corridor) is acceptable, but the targets in front will conceal those behind, or at least reduce the Effect. They are powerful weapons, but not all-powerful.

Example: Budda Budda Budda.... oops

Arnie, with Marksman [6] and a submachine gun, stumbles into a German trench during the First World War. Despite Arnie's cry of "Eat hot lead, you scummy krauts!", the referee accepts that they are surprised; Arnie will get one free attack before they can shoot back. There are five Germans, and he tries to shoot them all. His Marksman skill is raised to 7, because he is using a machine gun, but reduced to 5 because he is shooting at multiple targets, and the Effect is reduced from 9 to 7. Arnie succeeds in hitting and injuring three of the Germans, but there are no critical injuries or kills. All five will be able to shoot back in the next round!

It isn't possible to limit damage with shotguns, machine guns, or area effect weapons such as explosives or flame throwers, or with ANY attack on multiple targets.

|

If it is used, someone who rolls to hit a target without trying to hit a specific area should roll 2D6 for a random hit location as indicated above, and modify the Effect accordingly.

It is not possible to attack a specific hit location with machine guns or area effect weapons such as grenades, or while performing any form of multiple attack. Damage from these weapons should attack random hit locations.

Armour

| Armour | Effect | Notes |

| Bulletproof vest | -4 | projectile and blade attacks |

| Kevlar Body Armour | -6 | projectile and blade attacks |

| Bullet Proof Glass | -4 | projectile attacks |

| Medieval Plate Mail | -4 | melee weapon attacks |

| Medieval Chain Mail | -2 | melee weapon attacks |

| Motorbike Leathers | -2 | impact weapons (eg clubs) |

| WW1 Steel Helmet | -3 | attacks to head ONLY |

| Crash Helmet | -2 | impact damage to head ONLY |

The list to the right includes some modern armour as well as equipment that might be available in the late 19th century. The level of protection depends on the type of armour. Naturally only the area covered by the armour is protected; for example, motorbike leathers cover the torso, arms, and legs, but don't protect the head. A full-face crash helmet protects the head only. Similarly, body armour doesn't protect limbs or the head.

It's possible to imagine heavier armour, possibly as part of a powered suit, but generally speaking if it gives much more protection than this it should be treated as a building or a vehicle, not as personal armour. A good example of heavier armour is the steel plate legend ascribes to the outlaw Ned Kelly, which could allegedly resist rifle fire, but must have restricted visibility and mobility and restricted skills. The photograph of Ned Kelly's real armour, to the left, makes the legend seem somewhat suspect; a more realistic assessment would give it a -2 or -3 Effect modifier.

It's possible to imagine heavier armour, possibly as part of a powered suit, but generally speaking if it gives much more protection than this it should be treated as a building or a vehicle, not as personal armour. A good example of heavier armour is the steel plate legend ascribes to the outlaw Ned Kelly, which could allegedly resist rifle fire, but must have restricted visibility and mobility and restricted skills. The photograph of Ned Kelly's real armour, to the left, makes the legend seem somewhat suspect; a more realistic assessment would give it a -2 or -3 Effect modifier.

Remember also that armour is usually heavy and conspicuous, especially in a modern city. It will soon attract attention, both from the public and from the authorities.

Example: Tom Sloth And His Pneumatic Coveralls (2)

Tom Sloth's mechanical exoskeleton lets him lift things as though his BODY (normally 5) is 30. He decides to add some armour and use it to fight crime. The referee decides that plate mail will have a point of BODY for each point of Effect it stops, double that if it is going to be effective against bullets as well as simple impact forces. Tom wants to stop all bullets; the referee decides that this must mean it must reduce Effect by at least 10. The rebuilt suit will have 20 BODY in armour plate, reducing Tom's effective BODY (for lifting things etc.) to 10.

It's good armour and performs as specified. However, it hampers Tom considerably - he won't be very good at wrestling, dodging, etc., and has his vision severely restricted by its bullet-proof glass eye-slits. And he can forget any idea of using Stealth or disguises, swimming, or walking on any surface that won't support several hundred pounds of weight...

| ||||||||||||||

Some of the weapons shown have very high effect numbers, which go well off the "attack versus defence" table. This usually indicates an attack which will do maximum damage unless a 12 is rolled, or the effect number is somehow reduced; for example by distance (e.g. explosives), by the damage being spread to cover several targets (mini gun), or by armour.

Note that most unarmed attacks and some weapon attacks don't show death as a possible outcome; it simply isn't very likely in the course of a fast-moving fight. Referees should feel free to ignore the suggested result in unusual conditions; for example, if someone is attacked by a mob, while unable to resist, or is completely outmatched by his attacker.

While this game tries not to over-emphasise combat, this period produced some extremely odd weapons, as might the circumstances of a campaign. More detail is sometimes useful. Here are examples from FF VI and FF IX, the first historical and the second fictional:

Melee Weapons

Effect is based on BODY or skill.Weapon Multiple

TargetsEffect Damage Notes A B C Fist No [1] BODY [2] B B KO See above Kick No [1] BODY [2] B B F See above Wrestling No BODY [2] B KO KO / I See above Animal Bite No BODY+2 F I C See above Animal Claw No BODY+1 F I C See above Animal Horns No BODY+2 F I C/K See above [1] Using the Martial Arts skill it is possible to perform one fist and one kick attack in a single round against one target, or against two targets that are close together. Against two targets the attacks are at -2 Effect. [2] Users of the Martial Arts skill can use BODY or Martial Arts for Effect in these attacks, whichever is better.

Club Max 2 [3] BODY+1 F F KO/K Eg. Cricket Bat Spear No Melee F I C/K e.g. bayonet on rifle. Axe No BODY+2 F I C/K Sword Max 2 [3] Melee+1 F I C/K Dagger No Melee+1 F I I/K Eg. flick knife Whip No Melee/2 B B F Chair No Brawling B F I/KO Broken bottle No Brawling+1 F F I Nunchuks Max 2 [3] M. Arts B F KO/K Martial arts skill ONLY Staff Max 3 [3] Melee+2 F I KO/C [3] Targets must be within 5ft. Multiple attacks are at -2 Effect. Multiple attacks are available with the Martial Artist skill ONLY. Range For all melee weapons, targets are TOO CLOSE if they block effective use of the weapon; within a couple of feet for swords and axes, within 6 ft for whips (a lousy weapon, despite Indiana Jones), and so forth. If unsure, give players the benefit of the doubt.

Projectile Weapons

Effect is usually based on skill (for thrown weapons), on BODY (for longbows and thrown axes), or on the weapon rather than the user for firearms etc.Weapon Multiple

TargetsEffect Damage Notes A B C Spear No Melee F I C/K Thrown Axe No BODY+1 F I C/K Thrown Dagger No BODY+1 F I C/K Thrown Shuriken Max 3 M.Arts ONLY B F F Thrown Boomerang No Marksman B F KO/I Thrown Cricket Ball No Marksman B F KO/I Thrown Longbow No [4] BODY+1 F I C/K Hunting bow Crossbow No 7 F I C/K Military bow [4] Maximum 2 targets if attacking with Martial Arts skill. Small handgun Max 2 [5] 6 F I C/K e.g. .22 revolver Big handgun Max 2 [5] 6 I I C/K e.g. .38 revolver Huge handgun Max 2 [5] 8 I I C/K e.g. .45 revolver Small rifle No 5 F I C/K e.g. .22 rifle Big rifle No 7 F I C/K e.g. Winchester Huge rifle No 9 I C K e.g. Elephant gun. Small Shotgun Max 2 [5] 4 F I I One barrel Small Shotgun No [5] 8* / 4

* short range ONLYI I C Both barrels Large Shotgun Max 2 [5] 7 F I C/K One barrel Large Shotgun No [5] 14* / 7

* Short range ONLYI C K Both barrels Machine pistol Yes [6] 7 F I C/K e.g. Schmeisser Submachine gun Yes [6] 9 F I C/K e.g. Tommy Gun Machine gun Yes [6] 11 F I C/K e.g. Gatling / Maxim Gun Harpoon No 15 I C C/K Non-explosive whaling Harpoon No 25 C C K Explosive whaling [5] Hand guns can be used to fire at two targets, or twice at one target. If firing at two separate targets each attack is at -2 to hit. If firing two shots at one target there is no modifier. Each attack is resolved separately. Shotguns can fire twice at one target (no modifier to hit, small effect), fire at two different targets (modifier -2 to hit, small effect), or fire both barrels at once (+1 modifier to hit, big effect at SHORT range ONLY). In all but the last case the two shots are resolved separately. The doubled Effect of firing two barrels simultaneously is felt at short range ONLY! [6] Reduce Effect by 2 if fired at additional targets Ammunition Players will undoubtedly have their own ideas about the number of rounds in their weapons, and usually keep track without prompting. If you don't want to bother with bookkeeping it's perfectly acceptable to ignore the matter. As a rule of thumb six shots for all rifles and handguns, and three bursts or twenty single shots for machine guns, should satisfy most players. Gatling guns (including chain guns, rotary cannon, and mini-guns) cannot fire single shots, but the referee may wish to allow many more bursts to be fired. Range Normal range for all hand-thrown weapons, handguns, machine pistols, and submachine guns is 10-20 ft; normal range for bows, rifles, machine guns, and mini guns is 50-100 ft. Anything closer is at short range, anything further away at long range. Targets are too close if they are closer than the end of the weapon!

Area Effect Weapons

All explosives damage everything at full effect inside the radius shown, at effect -1D6 to double that radius, at effect -2D6 to three times the radius, and so forth. The effect of these weapons is not reduced if there are multiple targets.Weapon Damage

RadiusEffect Damage Notes A B C Stun Grenade 6 ft 8 B KO I+KO Hand Grenade 10ft 10 F I C/K Dynamite 10ft 10 F I C/K +2 Effect per additional stick. Mortar Shell 10ft 12 I C K Howitzer Shell 10ft 15 I C K Anti-tank mine 10ft 20 I C K Car Bomb 20ft 15 I C K Truck Bomb 20ft 20 I C K Flame Thrower 10ft 10 I C K No damage outside 20ft radius.

Exotic Weapons

Things that might conceivably come into play in a campaign, in no specific order.Weapon Multiple

TargetsEffect Damage Notes A B C Radium gun No 8 F I C/K Burrough's Mars Disintegrator Yes [6] 15 I C K Most SF Mini gun Yes [6] 8 I C K Terminator II Weapon Damage

RadiusEffect Damage Notes A B C Stun Gun 3ft 8 B KO KO Most SF Heat Ray 75ft 30 C K K War of the Worlds Black Smoke 500yd 10 C K K War of the Worlds Hydrogen Bomb 1 mile 40 C K K Not recommended!

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What's the BODY of a door? Of a bottle? Of the Queen Elizabeth? How much damage can a rabbit take (or dish out); a rhino; a blue whale? This section contains data on a range of common and uncommon objects, plants, and animals, which characters may conceivably encounter in the course of play.

Animals | |||||

| Rat BODY [1], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [1]; Bite, Effect 1, Damage A:B, B:B, C:F Wounds: Any wound kills | Rabbit BODY [1], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [1]; Kick, Effect 1, Damage A:-, B:B, C:B Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] C[ ] (Any Injury result is Critical) | ||||

| Domestic Cat BODY [1], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [4]; Claw, Effect 2, Damage A:B, B:F, C:F Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] C[ ] (any Injury result is Critical) | Small Dog BODY [2], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [3]; Bite, Effect 4, Damage A:B, B:F, C:F Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | ||||

| Big Dog BODY [3], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [5]; Bite, Effect 5, Damage A:B, B:F, C:I Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | Rottweiler BODY [4], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [7]; Bite, Effect 6, Damage A:F, B:I, C:C Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | ||||

| Note that the stealth of animals (especially small animals) is often considerably higher than BODY/2. Customised dogs and canine adventurers are discussed in an appendix below. | |||||

| Cobra BODY [2], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [6]; Poison, Effect 8, Damage A:I, B:C, C:K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | Anaconda BODY [6], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [7]; Wrestle, Effect 8, Damage A:I, B:I, C:C Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | ||||

| Lion or Tiger BODY [7], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [9]; Bite, Effect 9, Damage A:F, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | Horse BODY [7], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [4]; Kick, Effect 7, Damage A:B, B:F, C:I/C Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | ||||

| Bull BODY [8], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [10]; Horns Effect 10, Damage A:F, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | Bear BODY [8], MIND [2], SOUL [2] Brawling [10]; Claws/Bite, Effect 10, Damage A:F, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] Armour thick fur -1 Effect | ||||

| Rhino BODY [9], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [10]; Horn, Effect 10, Damage A:F, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] Armour thick skin, -2 Effect all attacks | Elephant BODY [10], MIND [2], SOUL [2] Brawling [6]; Tusks, Effect 10, Damage A:F, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] Armour thick skin, -2 Effect all attacks | ||||

| Alligator or Crocodile BODY [8], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [8]; Bite, effect 8, Damage A:F, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] Armour thick skin, -3 Effect all attacks | Dolphin or Porpoise BODY [8], MIND [3], SOUL [2] * Brawling [8]; Butt, Effect [8], Damage A:B, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | ||||

| Killer Whale BODY [15], MIND [3], SOUL [2] * Brawling [12]; Bite, Effect 15, Damage A:I, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] Armour thick blubber, -2 Effect all attacks | Blue Whale BODY [25], MIND [3], SOUL [2] * Brawling [10]; Butt, Effect 20, Damage A:I, B:C, C:K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] Armour thick blubber, -3 Effect all attacks | ||||

| * If dolphins and whales are intelligent in your campaign, you may wish to change MIND and SOUL ratings and add more skills, such as Linguist or Actor (singer). | |||||

| Tyrannosaur BODY [15], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [15]; Bite, Effect 16, Damage A:I, B:C, C:K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | Diplodocus BODY [20], MIND [1], SOUL [1] Brawling [15]; Butt, Effect 16, Damage A:B, B:I, C:C/K Wounds: B[ ] F[ ] I[ ] I[ ] I[ ] C[ ] | ||||

| Dinosaurs are discussed in considerably more detail in the worldbook for FF III. | |||||

Plants | |||||

| Cabbage BODY [1] | Sapling BODY [3] ** | Young tree BODY [8] ** | |||

| Large tree BODY [10-20] ** | Giant redwood BODY [30-50] ** | Giant flytrap BODY [8], Bite Effect 6, Damage A:B, B:F, C:I | |||

| ** Axes attack a portion of the BODY of a tree equivalent to the Effect of the weapon. For example, an axe with Effect 6 attacks 6 BODY of the tree, succeeding on a 7 or less. If successful, that much of the BODY of the tree is destroyed. Some trees have thick bark which may act as armour, or other defences. | |||||

Everything Else | |||||

| Internal Door BODY [6], lock Difficulty [4] | Street Door BODY [8], lock Difficulty [5] |

Church Door BODY [12] Lock Difficulty [8] | |||

| Piggy Bank BODY [1], Lock Difficulty [2] | Household Safe BODY [10], Lock Difficulty [10] | Bank vault BODY [20] Lock Difficulty [15] | |||

| House BODY [20] | Warehouse BODY [75] | Skyscraper BODY [200] | Household Table BODY [6] (wood) | Household Chair BODY [3] (wood) | Armchair BODY [4] |

| Garden table BODY [8] (iron) | Garden chair BODY [8] (iron) | Park bench BODY [8] (wood & iron) | |||

| Bottle BODY [1] | Motorbike BODY [4] (1900s) | Car BODY [10] | |||

| Truck BODY [15] | Bulldozer BODY [20] | Tank BODY [25] Armour reduces Effect all attacks -8 | |||

| Liner BODY [100] | Airship BODY [50] | Spaceship BODY [100] | |||

| Many of the Forgotten Futures collections describe vehicles including dirigibles (FF I, FF VII), various types of spacecraft (FF II, FF IX) and flying machines (FF II, FF III, FF VII, FF IX), and time machines (FF IX). Usually these descriptions add considerably more detail! | |||||

SO far these rules have said a lot about rolling dice, but little about the real meat of a role playing game; the opportunity to take on a completely different personality in a world of the imagination. Since most scientific romances were written by Victorians and Edwardians, characters have a tendency to fall into stereotyped behaviour which isn't necessarily changed if they are set in the future. Here are a few of the principal elements of this behaviour:

People in inferior positions accept that they are underlings. They are happy to be employed; the idea of bettering their position, over and above promotion within their workplace, is somehow abhorrent. This attitude is especially prevalent amongst servants and others in intimate contact with their social "superiors". For examples see the roles played by Eric Sykes in "Monte Carlo Or Bust", Peter Falk in "The Great Race", and Gordon Jackson in "Upstairs, Downstairs".